The Fight for Funding:

Understanding prevention and the continuum of care is critical for anyone in the mental health and substance use field. A shift in perspective from reactive crisis management to proactive support can lead to better outcomes for individuals, families, and communities. Today we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of prevention and harm reduction, explain where they fit in the broader system of care, and shed light on the challenges they face in the current political climate.

Prevention, in a public health context, refers to any action taken to promote health and well-being and to prevent the onset of illness, injury, or poor health outcomes. It's about being proactive rather than reactive. Instead of waiting for a problem to occur, prevention focuses on addressing the risk factors that could lead to an issue and strengthening the protective factors that promote positive outcomes. For example, in mental health, prevention could involve teaching coping skills to young people before they experience significant stress or training community members in evidence-backed trainings such as Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) and Youth Mental Health First Aid. In substance use, it could mean providing educational programs about the risks of drug use to at-risk populations.

The legislative challenges in funding prevention are significant. While it's widely accepted that "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," funding often reflects the opposite. The majority of government health spending goes towards treatment and crisis care, leaving prevention chronically underfunded. This is due to several factors:

Political Optics: It's often easier for politicians to rally support for and demonstrate the tangible results of treatment programs for people who are already struggling. A new treatment center or a medication that saves lives in an emergency is a visible, immediate success. In contrast, prevention's success is often measured by something that doesn't happen—a life not lost, an addiction not formed, a crisis not experienced. This makes it a less "sexy" or easily quantifiable win for policymakers.

Siloed Funding: Public health funding streams are often "siloed," meaning they are dedicated to specific diseases or issues. For example, a grant might be available for infectious disease control but not for a broader chronic disease prevention program. This "disease-specific" funding limits flexibility and investment in cross-cutting capabilities like early intervention or community-wide wellness initiatives.

Budgetary Cuts: Dedicated funding streams for prevention, such as the Prevention and Public Health Fund established by the Affordable Care Act, have been repeatedly cut and diverted to other purposes over the years. This instability makes it difficult for state and local health departments to plan and sustain long-term prevention efforts, leading to a constant cycle of crisis response. The United States simply gets the health outcomes it chooses to pay for, and historically, it has not chosen to invest sufficiently in prevention.

Proposed Federal Funding Cuts: Let’s take a look at the proposed federal budget for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This proposed budget includes significant cuts to or the complete elimination of many programs currently funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) through competitive grants. These grants, known as Programs of Regional and National Significance (PRNS), are crucial for funding innovative programs that address specific community needs. The proposed cuts, which could amount to over a billion dollars, would hit substance use prevention, mental health, and treatment programs hard. For instance, a program that trained tens of thousands of first responders and community members in administering overdose reversal agents would be eliminated, as would programs focused on providing services for pregnant and postpartum women with substance use disorders. This is a perfect illustration of how political debates over federal spending—often focused on deficit reduction—can directly threaten prevention and intervention efforts, prioritizing short-term financial savings over long-term public health.

Prevention is the proactive foundation of public health. By investing in strategies that address risk factors and enhance protective factors, we can stop problems before they start. Unfortunately, this proactive approach faces significant legislative hurdles. Politicians often prioritize visible, short-term solutions like treatment centers over the long-term, less tangible benefits of prevention programs. This, coupled with unstable funding streams and a "disease-specific" mindset, means prevention remains chronically underfunded. Overcoming these challenges requires a shift in political will and a greater public understanding that investing in prevention saves both lives and money.

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled”

Understanding the Continuum of Care:

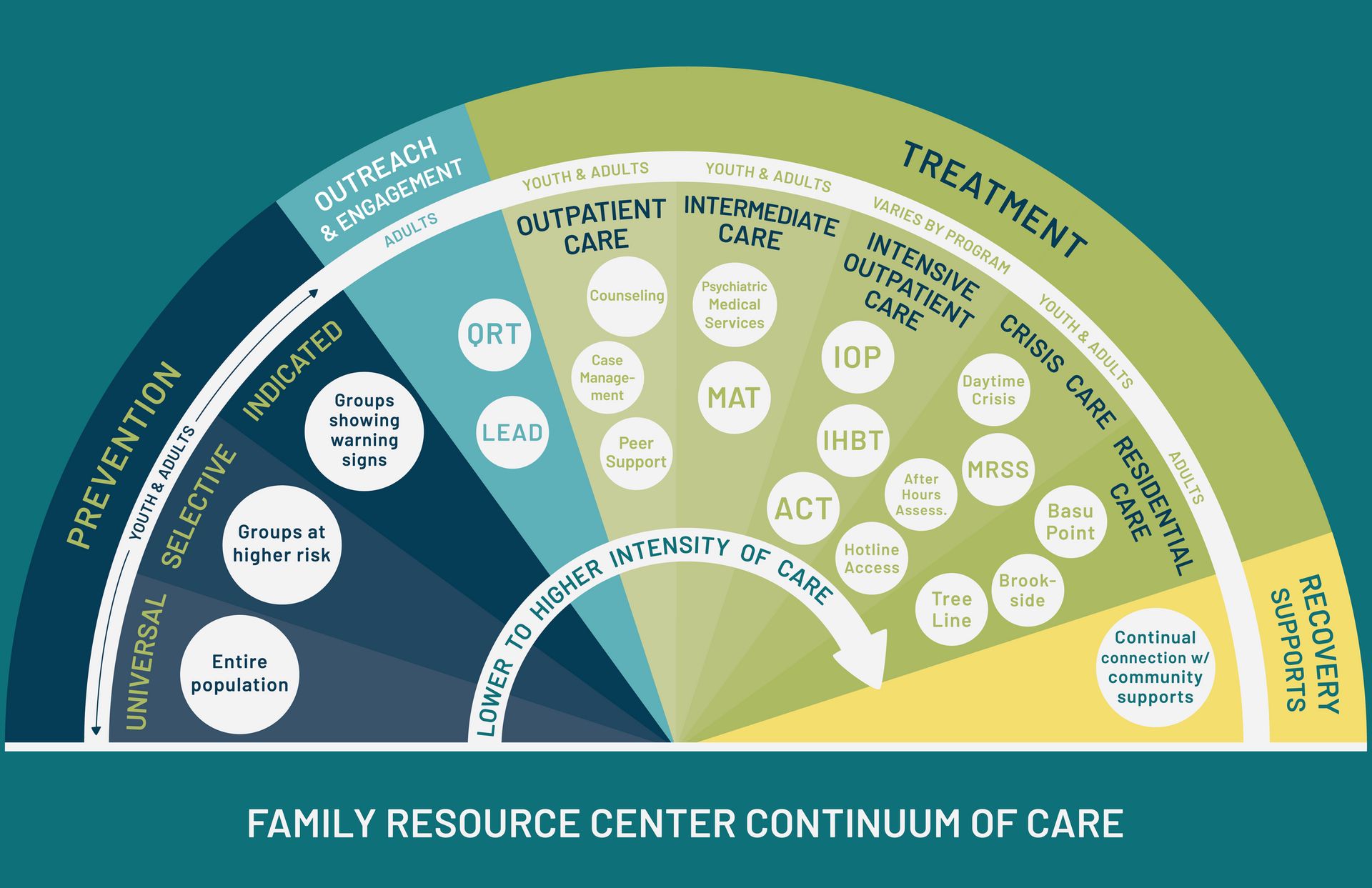

The continuum of care model is a framework that organizes and defines the full range of behavioral health services, from promotion and prevention to treatment and recovery. It emphasizes that a person's journey is not linear and that they may move between different levels of care as their needs change. The four main areas of this model are:

Health Promotion: These are interventions that aim to foster a person's well-being and empower them to make healthy choices. This can be as simple as an after-school club that promotes positive social skills or a wellness campaign in a community. Health promotion is universal; it's for everyone, regardless of their risk level.

Prevention: This is the core focus. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) breaks down prevention into three categories:

Universal Prevention: Interventions for the general public or entire populations that have not been identified as high-risk. This could include school-based substance use education for all students or a public awareness campaign about the importance of mental health.

Selective Prevention: Interventions for a subgroup of the population whose risk of developing a disorder is significantly higher than average. An example would be providing a stress management workshop specifically for children of parents with a mental health diagnosis.

Indicated Prevention: Interventions for individuals who are exhibiting early signs of a disorder or have been identified as high-risk. An example would be providing counseling to a young person who has a history of trauma and is starting to exhibit concerning behaviors.

Treatment: This part of the continuum provides clinical and supportive services for individuals who have already been diagnosed with a substance use disorder or mental health condition. This includes things like outpatient therapy, intensive residential programs, and medication-assisted treatment.

Recovery: The final stage, which often happens concurrently with treatment, provides comprehensive, long-term support to help individuals sustain their recovery and prevent relapse. This can include peer support groups, housing assistance, and vocational training.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: The establishment and rollout of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the United States provides a clear example of the continuum of care in action. While 988 is often viewed as a crisis response tool (part of the treatment and recovery components), it also functions as a powerful prevention and early intervention mechanism. For those with ideation but no immediate plan, a call to 988 is a form of early intervention—it provides support before a crisis fully escalates, potentially preventing a visit to the emergency room or a more intensive, costly intervention. It also connects individuals to local resources for ongoing support (recovery). On a broader scale, the national publicity and availability of 988 help to reduce the stigma around seeking mental health support (health promotion), making it more likely that people will reach out for help at earlier stages of distress. The 988 lifeline is an excellent, tangible example of a national initiative that is designed to work across the entire continuum of care.

Prevention is not a standalone part of this model; it's the foundation. By strengthening prevention efforts, we can improve outcomes across the entire continuum of care. When prevention is effective, it reduces the number of people who need treatment in the first place, thus alleviating the burden on an already strained treatment system. For those who do need treatment, effective early prevention can lead to less severe issues that require less intensive and costly care. It also creates a system where individuals are more likely to seek help earlier because the stigma has been reduced and they are already familiar with the concept of seeking support. In essence, a strong prevention system saves lives and money by reducing the number of people who fall into the more intensive and costly stages of the care continuum.

The continuum of care model offers a holistic view of behavioral health, ranging from health promotion to long-term recovery. Prevention is not just one part of this model; it's the cornerstone. By strengthening universal, selective, and indicated prevention efforts, we can reduce the number of people who ever need intensive treatment. This not only lightens the load on our overburdened treatment systems but also improves outcomes for everyone. A strong prevention framework creates a healthier community, reduces stigma, and makes it more likely that individuals will seek help early, leading to less severe issues and a smoother path to recovery.

Misperceptions about Harm Reduction:

Harm reduction is a pragmatic, non-judgmental approach that aims to reduce the negative consequences associated with substance use. It's built on the understanding that while abstinence is a valid and important goal for some, it is not always a realistic or immediate goal for everyone. Harm reduction meets people where they are and focuses on keeping them alive and as healthy as possible. The central principle is that any positive change, no matter how small, is a good step.

This is a point of large misconception, and this misunderstanding has a direct impact on political policy and local prevention efforts.

Myth: Harm reduction enables or encourages drug use. This is the most common and damaging misconception. The reality is that studies consistently show that harm reduction programs, such as syringe exchange services, do not increase drug use. Instead, they serve as a critical point of contact between people who use drugs and the healthcare system. By providing clean needles, fentanyl test strips, and access to naloxone (a life-saving overdose reversal medication), these programs prevent the spread of infectious diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C and save lives. This approach recognizes that a person must be alive to have the opportunity to pursue recovery.

Myth: Harm reduction is in opposition to abstinence and recovery. This is a false dichotomy. Harm reduction is not an "either/or" situation; it's a "both/and" approach. Harm reduction strategies are often the first step on the path to recovery. By building trust and providing a non-judgmental space, these services can connect individuals with treatment programs they might not have otherwise sought out. Many people who work in harm reduction have been in recovery themselves and understand the complexity of the journey.

These misconceptions create significant barriers to implementing effective policies. Politicians, influenced by public opinion rooted in these myths, may refuse to fund or even actively work to shut down harm reduction services. This leads to a lack of resources for life-saving programs like overdose prevention centers and syringe services. This not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) attitude often manifests as local opposition to harm reduction services, despite evidence that these services can actually improve community safety by reducing public drug use and improper disposal of needles. The moralistic viewpoint that frames addiction as a personal or moral failing, rather than a public health issue, fuels the push for punitive measures and supply-side solutions (e.g., trying to arrest our way out of the problem) instead of evidence-based, compassionate care. This ultimately leads to more preventable deaths and a more fractured system of care.

Debates over Overdose Prevention Centers (OPCs): The political and community-level debates surrounding Overdose Prevention Centers (OPCs), sometimes called supervised consumption sites, are a perfect case study for the misconceptions about harm reduction. While a few cities, most notably New York City, have opened OPCs, there is ongoing legal and political pushback to expanding them. Opponents often claim that these centers "enable" drug use and will lead to an increase in crime and public drug use in the surrounding neighborhoods. This argument, while politically potent, often ignores public health data. Proponents, in contrast, point to international evidence showing that OPCs significantly reduce fatal overdoses, prevent the spread of infectious diseases by providing clean equipment, and connect individuals with medical and social services, including treatment. The debate over OPCs is a direct reflection of the conflict between a punitive, criminal justice-focused approach and an evidence-based, public health-focused harm reduction strategy. This national-level debate demonstrates how the misconception that harm reduction enables use directly impacts policy and local efforts to save lives.

Harm reduction is a pragmatic, compassionate approach that saves lives by meeting people where they are. It's not about encouraging substance use, but rather about minimizing its negative consequences and building trust with individuals who may not be ready for or interested in abstinence. The misconception that harm reduction enables drug use is a major barrier to its implementation. This misunderstanding fuels political opposition and leads to a lack of funding for critical services like naloxone distribution and syringe exchange programs. A more compassionate, evidence-based understanding of harm reduction is essential to creating policies that prioritize saving lives and promoting public health over punitive measures.

Become a Pioneer of Change

Finding out what prevention efforts are available in your area is the first step toward making a tangible impact. While state and national resources are important, local initiatives often have the most direct effect on the people you interact with daily. Here's a guide to help you find and engage with local prevention work:

1. Start with State and Local Public Health Departments: Your state's Department of Public Health and Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (or their equivalents) are the primary sources for information. Their websites often have a "Programs and Services" or "Prevention and Health Promotion" section. Look for directories of local mental health authorities (LMHAs), regional behavioral health action organizations (RBHAOs), or prevention coalitions. These organizations are typically funded by the state to provide services in your specific area. They can offer a wealth of information about local resources, from school-based education programs to community-wide campaigns.

2. Explore Grassroots and Non-Profit Organizations: Many of the most effective prevention efforts are led by community-based non-profits. Organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and Mental Health America (MHA) have local affiliates across the country. Their websites often feature a "Find Your Local Affiliate" tool where you can search by ZIP code. These affiliates are excellent resources for support groups, educational workshops, and community-level advocacy. Similarly, seek out local chapters of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) or youth-focused groups that work on topics like anti-bullying, positive youth development, or substance-free events.

3. Look for Community Coalitions: Prevention work is often most effective when it is a collaborative, community-wide effort. Look for "community coalitions" in your area. These are often grassroots organizations made up of diverse stakeholders, including parents, law enforcement, educators, and healthcare professionals. They typically have a strategic plan to address specific local issues, such as underage drinking or youth mental health stigma. You can often find them by searching online for "[Your City/County] substance abuse prevention coalition" or "community wellness alliance."

4. Utilize National Directories and Search Tools: National government agencies and non-profits provide powerful search tools to help you find local services. For example, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) operates a Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. While this tool is primarily for finding treatment, it can also lead you to facilities that offer early intervention and prevention programs. Similarly, a search on a site like Youth.gov or the CDC's prevention resources can offer insights into evidence-based programs that may be implemented in your local schools or community centers.

By taking these steps, you can move from a general understanding of prevention to actively supporting the tangible, life-saving work happening in your own community.

In essence, understanding mental health and substance use challenges is about more than just responding to a crisis. Prevention and harm reduction are not side issues, but crucial components of a holistic continuum of care.

The current political landscape often favors visible, short-term solutions, leading to underfunded prevention efforts. This is a missed opportunity, as proactively addressing risk factors can save lives and ease the strain on our healthcare system. The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is a great example of a resource that operates across the continuum, providing both immediate crisis support and a pathway to long-term wellness.

Similarly, harm reduction is a vital, evidence-based strategy that saves lives by reducing the negative consequences of substance use. The ongoing debate over Overdose Prevention Centers highlights a common misconception—that harm reduction enables drug use—when in reality, it provides a safe point of contact for individuals who may one day be ready to seek recovery.

By championing prevention and embracing harm reduction, we can advocate for a more compassionate and effective system. Your role is to be a bridge—to help individuals before a crisis hits and to connect them to the right services, wherever they are on their journey. Your knowledge gives you the power to make a real difference, turning your understanding into actionable support for the community. Let's work together to create a society that values mental health wellness just as much as physical health.

FROM THE FOUNDER

Thank you for taking the time to read and enjoy Simplified Weekly Newsletter. A lot of effort has gone into hand selecting interesting and dynamic content to deliver to you.

If you enjoy what you see here I encourage you to visit our other social media accounts below for more or share the newsletter with family or friends!

Thank you,

-Zach Nailon, Simplified Newsletter